My public journalism is made possible thanks to the generosity of my paid subscribers. If you are receiving this post for free, please consider upgrading to paid. For $9 a month (less than a cup of coffee each week) will not only give you access to my documentaries, interviews and premium posts, you will get to join a group of New Zealanders in our chatroom who comment on posts and discuss the issues that are important to all us who want to live in a fairer,more democratic society.

Over the last year or so I have become increasingly concerned with the use of the term “Social Investment” that has come to drive social policy in our country, because, from information I have gathered, it is kneecapping social services in a host of areas - particularly in those related to the long-term social needs of the most vulnerable members of our society.

So, I thought today I would unpack this term “Social Investment” to explain why I am so unhappy with it and, yes, buckle up because what follows involves a fast ride over the last one hundred or so years of our social history.

The History of the Social Investment Concept in New Zealand

There was a time when we talked about Social “Welfare” in reference to all the social services our country provides, from free hospital care to benefits and pensions – you name it.

It began in the 1930s and 1940s and was based on principles of universalism and state responsibility for social wellbeing, and the post-WW2 decades saw the expansion of state-provided health, education, and social services.

As this is a post and not a Ph. D. thesis, forgive me if I truncate the range of factors in the early 1900’s that led to the development of the New Zealand Welfare State (some of the benefits of which we still enjoy today.)

In the wake of World War1, (in which more than 18,000 New Zealand men died) the Spanish flu killed 9000 people within a couple of months, followed by the Great Depression of the 1930s. So after decades of collective misery the idea that we should club together to look after each other in bad times took hold. That widows and their children ought to be supported with a benefit, the elderly should receive a pension, and workers, who got sick or injured ,or became unemployed should be financially supported by the government. In short, the big things in most people’s lives such as public health, housing and education became the responsibility of central government instead of individuals having to fend for themselves in troubled times with whatever money they could muster..

Of course this Social Welfare concept cost a lot of money, so taxes were much higher than today, with healthy workers and producers contributing towards the social safety net that they themselves, one day, might come to rely upon.

It would be a mistake, however, to see the 1930s reforms as simply being about income support. There was also a strong emphasis on employment and economic development. There were major changes in the trade and labour markets, with increasingly tight quantitative controls on imports alongside a much more centralised wage fixing regime. Together, these aimed at improving the ability of income from employment to provide adequate income for the worker and his or her family – “welfare by other means” – as well as fostering the growth of the industrial sectors.

After World War 2 the idea that the state had an obligation to support its citizens in coping with serious problems –perhaps as a form of quid pro quo for the efforts of all classes in successive wars- became cemented in as a core belief in our society. And I was one of the children lucky enough to be born in this post-war era where my working class parents got a 3 % loan for 40 years by cashing in the family benefit to pay for the the deposit on the building of a brand new home in Spreydon Christchurch. So I got a room of my own, never went hungry, got free medical care, and a free education up to and including university.

In 1972 a Royal Commission on Social Welfare recommended that the welfare system should ensure that “everyone is able to enjoy a standard of living much like the rest of the community and is thus able to feel a sense of participation in and belonging to the community.”

Enter Neoliberal Economics

I’m going to skip a decade now, to go to the mid 1980’s and then through to the 1990’s, when my generation began taking control of central government and the economy. And what did we do? Did we ensure our children would receive the same universal collective care and boost up in life that we got? We did not.

What we did was change the rules about what our obligations and duties were with respect to our fellow New Zealanders. In short, we embraced the economics and politics of selfishness that is called Neoliberalism, which largely promotes the rights of the individual over the public good. (Something by the way that David Seymour’s Regulatory Standards Bill seeks to embed into our laws.)

In the early 1980’s the neoliberal economic revolution began in the USA under President Ronald Reagan and in the UK under Margaret Thatcher, which saw the demise of the dominant post-war economy theory of John Maynard Keynes, who saw government as the driving force of the economy, replaced by the counter beliefs of Fredrich Hayek and Milton Friedman who argued that governments should get out of the marketplace because “ free “ markets would lead to the most efficient outcomes for society.

Neoliberal economics reached New Zealand via the 1984 Lange/ Douglas Labour government and was put on steroids by the subsequent National Bolger /Richardson government that followed it in the 1990’s.

The role of government in people’s lives was drastically reduced, benefits were cut, and lots of state utilities were renamed as state “assets “and sold off to the highest bidder. Taxes were reduced, and the State’s social message changed from “ Don’t worry we’ve got your back” to “ You’re on your own kid”.

I remember when I was making my documentary Mind the Gap ( about the huge disparity between the mega rich and the struggling poor that neoliberalism has created in our country ) finding the 1986 Treasury Paper that advised the government that “education was a private good, not a public good” and therefore people should pay for their own tertiary education. How could they possibly argue that, when life in our country had so clearly benefitted from educating our children as far as their abilities would allow?

And it wasn’t as though we got our tertiary educations scot- free with no strings attached. Many of us were bonded by the government to work in schools, hospitals, social work organisations or rural communities, for the same number of years as we received financial help to go to University or Polytech. The social gift came with an obligation to do our social duty. The result ? Better social services and few, if any of us, left University with the huge financial debt many of today’s students bear.

In short, through a raft of economic and policy changes during the 80’s and 90’s, our cooperative WE society was replaced by the ME society we have today, and with it went the idea of the universal social safety net - replaced by a two teir social system in which the wealthy buy income replacement insurance and private health care, while everyone else gets diminished care and protections thanks to a lowered tax take.

Within a generation our egalitarian society morphed into a divided one of HAVES and HAVE NOTS , where success in life became equated with how much money you make, and the word “vocation” slipped from our language that had become increasely commodified.

We are what we say – “Social Welfare” Becomes “Social Investment”.

One of the things I noticed over the 1980-90’s period was how our language came to reflect the self-centredness of the new ME society. Public Utilities such as our electricity and telecommunications networks, were renamed as ““State Assets”, because you can’t sell a utility but you can sell an asset.( As Roger Douglas and Ruth Richardon both did!)

“Personnel Managers” whose job, in large measure, was to liaise between management and workers plus take an interest in staff well- being, became “Human Resource Managers” reflecting the new depersonalised attitude toward empolyees who were now regarded as a bottom line expense on a company spreadsheet that could be reduced or removed to increase shareholder profits. And thanks to National’s 1991 Employment Contracts Act, which abolished compulsory unionism, wages were progressively lowered and life became tougher for the majority of us.

As part of the commodification approach to our New Zealand way of life the term “ Social Welfare” gave way to the term “Social Investment “ which was ushered in by the Fifth National Government under Prime Minister John Key and Finance Minister Bill English, who championed the idea that government should use data and evidence to target social spending.(Presummably born of the problem of how to distribute a much reduced tax take more effectively, rather admit neoliberalism was failing to provide for the well-being of everyone in our country .)

The National Government formally launched its Social Investment Package in 2015, and at its core the initiative was about using administrative data—particularly from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), a large research database managed by Statistics New Zealand— to identify at-risk populations and direct services accordingly.

The Ministry of Social Development (MSD) pioneered the use of actuarial valuation—a technique borrowed from the insurance industry—to estimate the long-term fiscal liability of individuals remaining on welfare, with the goal of reducing future costs by investing in effective early support.

In short, the policy was to get the biggest social bang for the reduced tax bucks with the result that not-for-profit, community based, social service providers were suddenly subject to a corporate paradigm with targeted contracts that tied them to results and measurable outcomes,

I find it interesting that upon leaving parliament the architect of the Social Investment approach to the provision of social services, co-founded a business called Impact Lab Ltd that their website says “ puts a dollar value on social impact with credible, sector-informed insights, giving organisations the confidence to make data-driven decisions.”

English Investment Trustee Limited owns 44.69 % of Impact Lab (all the director of which have the surname English), Maria English owns 5.13% and Simon English is a Director.

In November of 2024 chief executive Maria English told TVONE’s Q +A Impact Lab Ltd had completed nearly 300 assessments measuring what it called “social return on investment” and that her organisation's reports can cost charities up to $30,000, aim to demonstrate the long-term value of social services (to government) .See:

https://www.1news.co.nz/2024/11/17/the-price-of-doing-good-what-is-impactlabs-impact/

I mention this because whatever the term “Social Investment” was meant to deliver, it seems to me it has turned the act of caring for each other, which we once thought of as our duty, into a business.

What we think about our fellow human beings is reflected in the language we use when we talk to them or describe them.

For me, the term “Social Investment,” when applied to people in need, carries connotations of worth evaluation. What kind of return am I going to get out of supporting this group of people compared to that group of people. Who is more deserving of my tax money?

To put it bluntly, it seems to me that we have commodified our humanity.

We have diminished our responsibility and duty of care to each other because the politics and economics of selfishness has become wired into what both major poiitical parties now think they are about -which is to make life easier for big business and big money, in the completely discredited belief that giving tax breaks to the rich will magically trickle down to the poor; instead of being the elected representatives of the People to control the economy in such a way as to ensure the nation’s wealth, earned by the people, is spent on their well-being.

Conclusion

So, I’d like to see social policy currently being administered under the name of “Social Investment,” be guided instead by the concept of “Social Responsibility” or even, to use a that really out of vogue term, “Social Duty”.

Because in a civilised society we care for one another. We don’t begrudge them, demand they prove their worthiness, or exploit them by privatising their right to assistance.

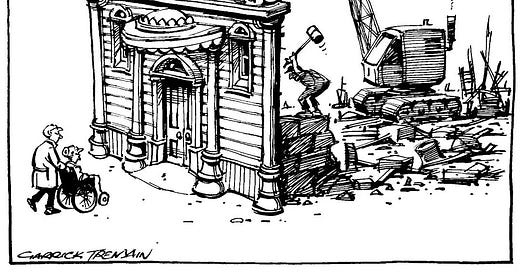

Today’s leading and highly pertinent cartoon is by Queenstown based Garrick Tremain.

This post is currently for paid subscibers. Thank you for supporting my public journalism . If it receives more than 80 “likes” it will me made free for anyone to read.

Please restack and share any posts you think are worthwhile as it all helps to build readership.

Couldn't agree more. The greed and selfishness of our 'leaders' is turning life into a misery for many, if not the majority, of New Zealanders, and those people apparently care not one bit about the horrors they have created. Like Bryan, I'm old enough to have benefitted from free education, and a health system that was one of the best in the world. Yes, it was funded by a high marginal tax rate - over 60% for the higher end of incomes - and as in the Scandinavian countries that still use that approach, everyone benefitted. The rich didn't curl up and die because they were losing a bit more of the cream, and the poor were safe, with stable homes, access to a doctor when needed, and schools that, in the main, gave all children a decent education. We have, as a society, gained nothing from neoliberalism, and we've lost our humanity.

Yes, I want a country, society, community that is fit for human habitation. We are now far far beyond this, and with the RSB it is going to get worse. I am not a commodity or a business, let alone a corporation.